Vision Debates: Are Dancehall Queens vulgar or skilful?

- by Nadine White -

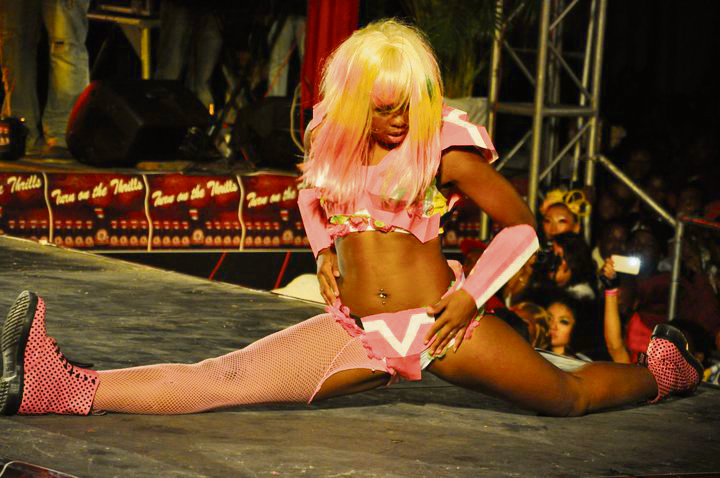

Scorned as a vulgar presentation of male fantasies and equally adored as one of the various colourful manifestations which underpin the vibrance of dancehall culture, Dancehall Queens (DHQs) are entangled in a web of opposing sentiments. Despite the negative opinion which DHQs typically attract from an ‘uptown’ demographic, their general story is one of success.

A worldwide phenomenon

The first DHQ was Carlene Smith, crowned in Jamaica in 1992. Following this, Big Head Promotions staged its first DHQ competition in Montego Bay/ Jamaica in 1996 and has been running ever since.

In 2002, history was made when Japanese dancer Junko Kudo became the first foreigner to take the crown, which lead to an influx of female dancers from all over the globe participating in the contest – making this, a transatlantic affair. Since then, the DHQ hype has taken off with contests being held all over Europe, Scandinavia, Russia, America and Japan, with ladies quite literally spreading far and wide. Pun intended!

Not only is this kind of dancing prevalent within the competitions, but it has infiltrated the more mainstream facets of dancehall entertainment, such as the music videos and dance trends. However, women jiggling and whining to the bass-line can offend. Some parents cry out against their children’s exposure to over-eroticized movements and sociological theorists have stated that this kind of dancing is an indication of a ‘crisis within the female’.

Robert Cooper spoke out against the DHQ culture in this way, addressing the matter, in a powerful article for the New African Magazine, a couple of years ago: “The clothes worn by dancehall queens have shrunk to less and less, while the dances have grown increasingly vulgar […]. It is time for Black women to reclaim their bodies and redefine their sexuality. The world should say full stop to sexually objectifying our sisters.”

Indeed, skimpy attire is a widely associated feature of DHQs. Paired with the lewd dance routines, it has caused some to question whether the status of ‘queen’ means that these women are seen as equal to their male counterparts or does it actually mean the opposite? English Feminist Sociologist Susan Manning (1997) argues that viewing the near naked female body in a public capacity is demeaning and de-powering.

White Aristocratic “Dancehall Queens”

On the other hand, in 18th century France, white upper class females (otherwise known as ‘Courtesans’) would frequent the male dominated arena of ‘the court’ and dance for their suitors, eventually gaining their companionship, affection and respect. In other words – these women would go and ‘look man’ by dancing for them! They did this completely out of free will and were not oppressed, in fact these women were bold – as opposed to stereotypically docile – and through their dancing, actually became to be treated as equals to men.

So, although the time, location and ethnicity of the women differ, the concept of dancing to entice the mass male audience can interestingly be applied to both the dancehall and a white, aristocratic setting. This begs the question ‘who is in control here, really?’ It would seem that women actually are! Furthermore, DHQs can be seen as a mutual, heterosexual celebration of the erotic in the female.

On a topic such as this, it was only befitting that ‘Vision Newspaper’ Co-Founder/Editor Francesca Quaas caught up with Jamaican dancer ‘Keiva Da Diva’ – one of the island’s more popular female dancers. Although not a ‘Dancehall Queen’ as we may know it, Keiva is certainly a ‘Queen of Dancehall’ and a true choreographer, having appeared in over 100 music videos, working with most of the dancehall artists in the game from Elephant Man, Bounty Killer to Konshens and Mr Vegas.

Survival of the fittest

Boldly declaring that “a female dancer has to work twice as hard as a man” – she immediately demonstrated one of the key qualities which she, herself, said that a female dancer must have to survive in dancehall – “boldness” and a steely determination to succeed.

On the topic of self-assertion, she went on to say, “Everyone has a right to express themselves”, adding “You have to consider that DHQs make the dancehall nice. I would agree that they are getting more… daring but I’m not going to bash them, it makes them eat their food”.

It has been said that Jamaican dancehall culture in its entirety can be used as a springboard for even greater prospects. Dancehall star Mavado recently spoke to Jamaican radio station ‘Irie FM’, on the importance of dancehall for the purpose of self-sufficiency. Making this statement in relation to the island’s ‘Noise Abatement Act’ he said, “When you make dancehall suffer you make the youths that eat off dancehall suffer”.

Being crowned DHQ can potentially give an opportunity for women to launch a career in a country which, for different reasons, does not always offer alternative job opportunities or a public purse to help support unemployed people. The informal economy which lies within dancehall is an important part for many Jamaicans to keep them and their families afloat.

Unofficial figures show that 10% of the population make a living through dancehall! For many, it is a means of survival and ‘riginal DHQ’ Carlene Smith put it best when she said: “I have made a lot of girls in the ghetto society say: ‘I can dance, let me make something of my life. I don’t have to wait on a man! ‘“

Silver-screen influences

Take the 1997 Jamaican hit movie ‘Dancehall Queen’ starring Audrey Reid, for example. Here is a “ghetto Cinderella story” of a modest ‘street vendor’ who manoeuvred through her impoverished circumstances via the opportunities that dancehall created, outsmarting and eventually escaping two particularly undesirably domineering male figures in her life by playing them off against each other! The film grossed over $160,000 in the USA alone and did extremely well overall, due to its gritty, easy-to-relate-to storyline.

West Indian Author & Professor Carolyn Cooper has argued that Downtown Jamaica’s DHQ contests are, in some ways, the answer to the uptown ‘Miss Jamaica’ beauty pageants, which lends weight to the idea that the concept of DHQs is more founded upon cultural resilience, than accidental ‘slackness’.

These regal women have effervescent personas and a long standing popularity within dancehall, meaning that most people have an opinion on them – from the ordinary party goer to reggae music contemporaries. Legendary DJ Daddy Ernie (of Choice FM) chimed in on this debate with no hesitation: “One of the many appeals of Dancehall Queens is that these are, typically, ordinary women. These women are confident and the dancing is very much a case of “here I am, look at me” than just blind slackness and vulgarity. They are about colourful self-expression and I don’t see anything wrong with that.”

One certainly should not be mistaken in thinking that every DHQ is an inwardly depressed damsel in distress, who wants to come out of an economically impotent situation. “None of these girls regard themselves totally seriously, it’s fun and it’s all very tongue-in-cheek – or wherever”, said Rick Elgood, director of the film ‘Dancehall Queen’.

‘The X Factor’

Despite the supposedly sexy grimace that a lot of black women wear when ‘bussing a whine’, we have to consider the idea that some DHQs actually dance because they want to! Seeming to encompass the swagger and confidence that most women would dream of possessing, they flaunt it; some argue that therein lies genuine power, the liberation of self-assurance.

Looking past that ‘barely there’ costume, multi-coloured wig, drawn-on eyebrows, false eyelashes and twelve inch stilettos, the one thing that remains certain is that these women can indeed dance.

If we consider the sheer physics of it all, then we can conclude that it does take skill to execute most of the moves displayed by DHQs. Therefore, where their dancing is concerned, its frankly more about dominance over one’s own body, than it is about being controlled. The fact that DHQs are, by trade, extremely disciplined dancers shouldn’t be overlooked.

The definition of ‘vulgar’ is: ‘lacking in sophistication and good taste; coarse and rude’ (Oxford Dictionaries, Oxford University Press, 2013) and is the term often used by those opposed to the dancehall culture to describe the overall style of Jamaican Dancehall Queens. However, how would they describe pop-divas in mainstream media and contemporary dance culture? In regards to the argued plight of DHQs, it then seems that they are no less emancipated than the likes of Beyonce and Rihanna who dance exactly the same way on our TV screen! The only difference is (maybe) money and nationality.

Irrespective of geography, our society has become desensitised to sex and raunchiness, full stop. Plus, I daresay that most girls and young women have the capacity to morph into their own DHQ in the common house party, rave or bar, once they’ve had a couple drinks and feel free to ‘express themselves’.

I daresay that ‘slackness’ itself is not sensational – the King of Dancehall (and ‘Slackness’) Yellowman put it best when he said “…but it’s just what happens behind closed doors “ ; and the reality of the situation is that the Jamaican culture is known for being ‘straight-to-the-point’. Dancehall Queens are no exception to this. Moreover, the issue of explicit behaviour does not start and stop in the “little but tallawah” Island of Jamaica, as it is just not that tallawah!

VISION DEBATES:

What is your view?

Send us your comments and/ or pictures, which we will release in our next issue:

admin@vision-newspaper.co.uk